In recent debates on the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) of the EU, culture has been ascribed a prominent role as a means to “soften” this policy field (while, at the same time, coordination of the military industries of the Member States and the setting up of multi-national battle groups lead to a “hardening” of CFSP.)

Out of a perspective on culture and the arts as a value in themselves, this political functionalisation might look as suspicious and inappropriate; however, this is not the view of this paper. On the contrary, it is argued that cultural politics always pursues political aims and that this fact in itself is not problematic: All democratic policies have to be subordinated to democratic political goals, and foreign policies aimed at making borders more permeable and at deconstructing essentialist identity constructions can further inclusive concepts of democracy.

However, it would be short-sighted and naïve to suppose that every use of culture and the arts within foreign policy making will, in fact, lead to a “softening” of this policy field. Such an approach would once again abuse the “deceptive placidity of culture” (Raunig 2007). Thus, in the following, two – rather ideal typical – forms of dealing with culture and the arts in foreign policy and their probable consequences will be described.

Culture and differentiation: The logic of an

exclusive club

In an opening statement at a conference on European cultural politics[1], Jose Manuel Barroso presented his view of European cultural identity in the following terms:

“The Preamble of the Constitutional Treaty states that Europe is ‘united in its diversity’. These words are both reassuring and ambitious. They are reassuring, because they positively acknowledge and thus protect the extraordinary richness of our national and regional cultures. (…) These words are also ambitious, because they emphasise that diversity does not mean division, but that it is rather the recognition of the richness of our diversity which enables us to unite. To put it differently, they commit us to establish the richness of our diversity as a structural element of our unity.” (italics added).

While diversity is recognized as a structural element in the European unity, this diversity is described as ours, i.e. there is an underlying logic of commonalities that differentiates us, even if diverse, from others – the truly different ones. This statement capturing the most recent developments of the EU as a political project follows a well trodden historical path of Europe’s differentiation based on what may be termed the logic of an exclusive club – a historical pattern of differentiating the European self from other entities based on a perceived commonality of culture as a bearer of shared principles and values.[2] In various guises, the logic of an exclusive club continues to be present in the EU’s territorial differentiation from others until today, above all through essentialist accounts and myth building about Europe as a historical cultural unit. The speech by the German federal Minister of Culture, Berndt Neumann, delivered to the above mentioned conference illustrates this well:

“Conveying a positive picture of Europe to people is a huge challenge. I am convinced that culture must always be at the very centre of all such efforts. Because Europe has always been a cultural unit.“

Culture as a basis for territorial differentiation transpires in various ways in the constructions of the EU’s relations with countries such as Morocco, Turkey or Russia (Neumann 1999, 1999, Diez 2004, Rumelili 2007).

In the decades following World War II culture has also been of key importance in Europe’s temporal differentiation from its others. Here, the object of differentiation was constructed not in territorial terms, but in relation to Europe’s own war-torn and fragmented past (Waever 1998). Through the emergence and success of the EU, Europe is perceived as having found a new set of principles and values of political organization that enabled it to move beyond the centuries of warfare and thus to subdue the dangers and tensions inherent in a system of nation states driven by a raison d’êtat logic and national interests (Fischer 2000, Leonard 2005). Europe hence differentiates itself from other political entities which continue living ‘in the past’, as it were.

However, this “post-modern” distancing from one’s own past does not make the EU immune from slipping back to the traditional mode of European differentiation based on a logic of the exclusive club. Some recent EU-reactions to situations beyond EU borders, such as the murder of the Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya in 2006, reveal a continuation of this pattern. Another quotation of Jose Manuel Barroso illustrates this well:

“The murder of this brave journalist [Anna Politkovskaya] is just one example of an increasing number of challenges to European values. Values like freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and tolerance. So my intention today in Berlin, the heart of Europe, is to issue a wake-up call in the defence and preservation of our values. We need to defend the European spirit of freedom.

(…)

… Together, let us defend freedom through dialogue between cultures, in Europe and the wider world. Let us listen. Let us offer a hand. But let us also assert that, as Europeans, we place our democratic values above everything else.”

Russia (and/or undemocratic elements within Russia) here play the role of the EU’s ‘temporal Other’ (cf. Neumann 1999) - a political entity which has not yet reached the EU’s stage of political development. EU’s temporal differentiation opens doors to a rise of a post-national form of Euro-nationalism. The very rise in awareness about this post-national culture, which the Europeans supposedly (should) share, may be the first step in the rise in ‘Euro-national’ awareness. Public statements on the temporally differentiated post-national identity of the EU are efforts to support the rise in the self-consciousness of the EU-community. For some, this qualifies as ‘Euronationalism’ (cf Garton Ash 2004b) with all its perils.

In the two modes of differentiation discussed here, culture helps to maintain the EU as an exclusive club in relation to outsiders. But how does it do so? What, from this perspective, is the role of culture and cultural products in the EU’s external relations? One can start by proposing that the sense of exclusivity of the EU is dependent on others’ perception. Hence, culture and cultural products are to generate or maintain the EU’s attractiveness (soft power) as a community with a unique institutional set-up enabling the peaceful and thriving co-existence of diverse national communities. For this purpose, cultural diplomacy and public diplomacy activities by the EU have been called for in recent years (Fiske de Gouveia 2005).

This public and cultural diplomacy is framed in terms of dialogue between civilizations or dialogue between cultures – all such efforts reconfirm the notion of the EU as an exclusive club, as a bearer of a distinctive culture/civilization, while others with whom the dialogue is sought are re-confirmed as representing other (non-European) civilizations and cultures. The goal of the dialogue is ultimately to change these others towards our model, thus, the universal value of European culture is confirmed.

Transcultural Exchange: The

Logic of Permeable Borders

As an alternative to the previous perspective, where culture plays the role of a mechanism cementing Europe’s imagined exclusiveness and thereby erecting boundaries and differentiating Europe from other communities, a different interpretation of the role of culture in the construction of ‘Europe’ focuses on its cross-community integrative aspects. The inner-outer dynamic of identity formation through transcultural relations provides an alternative to various forms of territorial and temporal differentiation of Europe from outside collectives. Several current policies in the EU’s external relations can be mentioned. First, the project of common spaces between Russia and the EU initiated in 2003 and implemented since 2005. It includes roadmaps for four common spaces in the fields of economy; freedom, security, and justice; external relations; and research, education and culture.[3] According to an early assessment (Emerson 2005), it is in particular the latter area, which is the most likely to have practical impacts on educational and cultural exchanges of various kind. From the Russian point of view, this is an attempt to create ‘greater Europe’ as a loose connection between the EU and a ‘Russian-led community to its east’ (Trenin 2005:8). The negotiators and the texts of the agreements avoided explicit references to ‘EU norms’ and hence allow for various interpretations of the directions that the co-evolution of the EU-Russia relations might take (Emerson 2005:4). This makes the common spaces between the EU and Russia conceptually different from for instance the EU Neighborhood policy, which builds on the asymmetry of relations and transfer of EU-norms. In a sense, the notion of common spaces hence also reflects the call by Batt et al. (2003:126-127) for a re-thinking of the messages and signals that the EU sends out to the neighboring societies from the paternalistic ‘you must become like us’ to a more partner-like ‘we will be with you’.

Second, an attempt to create a common space in the Mediterranean has been under way following the launch of the Union for the Mediterranean. Established on July 13, 2008, it comprises 43 countries including EU member states and states from the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean. The idea is to provide a framework for relations between the EU and its neighboring countries to the south on a more equal footing than was the case in the framework of the Barcelona process initiated in 1995. As president Sarkozy argued, the latter process “was an error”, because it was based on the logic of the North-South dialogue as it developed following decolonization, namely an unequal relationship where the EU decided on political initiatives and the countries on the southern shores of the Mediterranean were supposed to implement them. In this manner it merely maintained the societal divides between the EU and the southern neighbors.[4] The Union for the Mediterranean is to work on a different logic, as the Joint Declaration following the launch of the Union proclaimed: “Europe and the Mediterranean countries are bound by history, geography and culture. More importantly, they are united by a common ambition: to build together a future of peace, democracy, prosperity and human, social and cultural understanding.” Among the common projects to be implemented are a Euro-Mediterranean University and a student exchange program modeled on the Erasmus program.

Third, on a smaller scale, regional initiatives fostering the (re-)constitution of cultural regions across the formal borders of the EU such as the Transcarpathia region (between the Ukraine, Hungary, Slovakia and Poland) also provide a basis for mutual constitution and co-evolution of identitifications. Through such processes, the frontiers of the EU become fuzzy and represent an area of inclusion rather then exclusion (Batt and Wolczuk 2002, Zielonka 2006).

Cultural relations of this kind open up possibilities for the juxtaposition of conflicts and controversies within societies and thereby provide an alternative to the official images that governments are trying to promote.[5] Arguably, this is also the logic behind the planned establishment of ALEPH – a European agency to be based in Berlin aiming to promote networking between cultural actors and intellectuals from Europe and the Middle East. Such initiatives provide a basis for mutual openness and learning.[6] In this way, European culture in all its fragmented and individualized forms, and with all its controversies, provides more openings for connections with non-European societies. An open and integrative European cultural space may hence be forged.

Conclusions

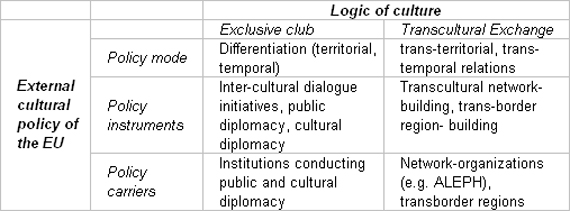

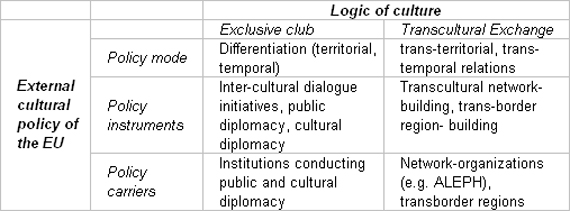

The table summarizes our discussion on the two key logics of culture in the EU’s external relations.

Table 1: The role of culture in the EU’s external relations

Culture has been a challenged concept in Europe and elsewhere, and

it has been playing an ambiguous role in political communities. One of the key

ambiguities relates to the dual role of culture in the building and

transcendence of boundaries between political communities. On the one hand,

culture creates bonds between community members and serves as a means of

boundary-building. On the other hand, culture connects people across formal

boundaries of political communities and thereby serves as a means of boundary

transcendence. This duality pertains also to the role of culture in the EU’s

external relations. Through the inclusion of cultural components the CFSP is

being ‘softened’ and that may have positive effects on the EU’s attractiveness

in third countries. At the same time, though, due to the ambiguities that

characterize culture and its uses for political purposes, the cultural

dimension of CFSP will remain a field of ambiguous political action and

ambivalent political outcomes.

References

Batt, J. and Wolczuk, K. (2002): Region, State and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe. London: Palgrave

Batt, J. et al. (2003): Partners and Neighbours: A CFSP for a Wider Europe. Chaillot Paper No. 64, Paris: EUISS

Diez, T. (2004): "Europe's Others and the Return of Geopolitics" Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 17(2):319-335

Emerson, M. (2005): “EU-Russia. Four Common Spaces and the Proliferation of the Fuzzy” CEPS Policy Brief No. 71, Brussels: CEPS

Fischer, J. (2000): “From Confederacy to Federation: Thoughts on the Finality of European Integration.” speech at Humboldt University, Berlin, May 12, 2000

Fiske de Gouveia, P. (2005): European Infopolitik: Developing EU Public Diplomacy Strategy. London: The Foreign Policy Centre

Gong, G.W. (1984): The Standard of “Civilization” in International Society. Oxford: Clarendon

Leonard, M. (2005): Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century. New York: 4th Estate

Neumann, I.B. (1996): “Self and Other in International Relations” in: European Journal of International Relations, 2(2): 139-174

Neumann, I.B. (1999): Uses of the Other. “The East” in European Identity Formation. Manchester: Manchester University Press

Raunig, G. (2008), Die falsche Sanftmut der Kultur. Anmerkungen zur Mitteilung über eine europäische Kulturagenda im Zeichen der Globalisierung, in: Kulturrisse 01/08. http://igkultur.at/igkultur/kulturrisse/1207745399/1210676092, 2009-01-14.

Rumelili, B. (2007): Constructing Regional Community and Order in Europe and Southeast Asia. London: Palgrave

Trenin, D. (2005): “Russia, the EU and the Common Neighborhood” CER Essays, London: Centre for European Reform

Wæver, O. (1998): ”Insecurity, Security, and Asecurity in the West European Non-War Community” in Adler, E. and Barnett, M. (eds.): Security Communities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 69-118

Zielonka, J. (2006): Europe as Empire. The Nature of the Enlarged European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press

[1] “Europe and Culture”, A Soul for Europe conference, Berlin, November 26, 2004.

[2] See Gong (1984), Neumann (1996, 1999).

[3] For more information see http://ec.europa.eu/external_relations/russia/common_spaces/index_en.htm

[4] Speech by President Sarkozy before the students of the National Institute of Applied Sciences and Technology, Tunesia, April 30, 2008 (available at http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/article-imprim.php3?id_article=11447)

[5] Illustrating this aspect in the work of the British Council, Davidson (2008:84) quotes a British Palestinian academic arguing that “If the British Council simply parrots what the Embassy says about Britain we are not interested. But there’s a Britain we’d like it to show us – the Britain of the million marchers against the [Iraq] war in February 2003.’ A similar logic was at play when the British Council invited young British photographers to depict aspects of Muslim life in Britain. They were entirely free to choose what aspects and how to portray and the result was an exhibition entitled ‘Common Ground’, which successfully toured various Moslem countries. As Davidson (ibid.) reports, “the resulting media debate suggested that this approach fostered a degree of interest and debate around shared values that a more didactic approach might not have achieved. A review in the Independent argued that the exhibition was ‘ground breaking . . . its impact on Arab viewers cannot be overestimated. For Saudi Arabia, it is the first significant collection to be imported from the West in more than three decades‘.“

[6] ALEPH “sees its task in initiating, fostering, and accompanying projects that bring the Jewish, Muslim, Christian, and secular cultures of the Middle East into contact with the cultures of Europe. The goal in this is to bring the Arabic-language, Jewish-Muslim heritage of the Enlightenment more strongly into European consciousness again. This would contribute to Europe's self-finding and to the shaping of a European future, which will be increasingly shaped by contact among the different cultures. The agency can take recourse to a large, diverse network of artists, intellectuals, and researchers from the Middle East and Europe who are already in contact with each other. … [ALEPH] seeks to demonstrate how cultural experience and knowledge can benefit European foreign policy: Europe as a service provider in the global dialogue of cultures” (from www.berlinerkonferenz.eu, italics added)